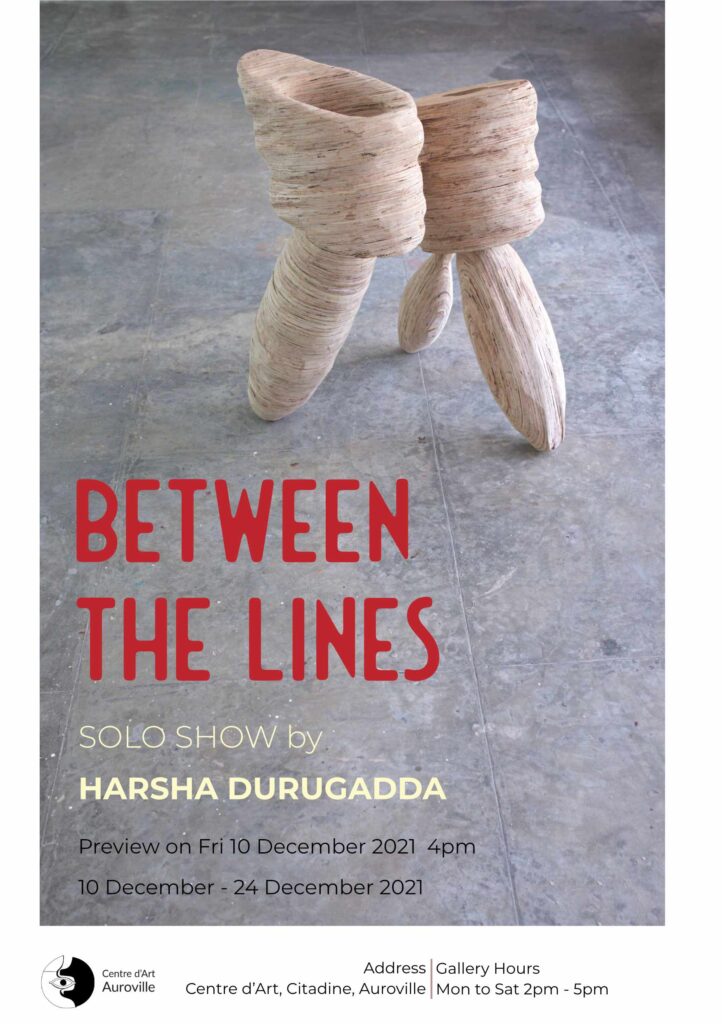

BY Harsha Durugadda

10th to 24th December 2021

Monday to Saturday 2pm-5pm

Opening on Friday 10th December at 4pm

Like so many more interesting artists, Harsha Durugadda’s work comes from a place of intense focus. This focus on the world around him does not lead him to conservatism; rather, it sharpens his view of his surroundings.

With an appreciation for sculpture kickstarted by growing up in a family of artists, he claims vernacular architecture- churches, temples, monuments- as one of his biggest influences. Yet his work also shows a singular resistance to the ideas of control that lie behind most of these great pieces of architecture. “As a civilization, religion has exploited the power of sculpture fully to hypnotize people with form and shape. This is where my work departs from and continues its journey into finding new meanings in form.” Durugadda describes his creations as “objects of enquiry into human behaviour,” that is, not something strictly visual, but a vision to be experienced holistically.

This thoroughly ‘natural’ quality is something that is difficult not to translate into an ‘anti-humanist’ ideal of art- as the artist says himself, “we are nature”- so it was hardly surprising to hear of the influence of indigenous arts and lifestyles on his own. While Harsha himself prefers the term ‘non-human planetary approach’, his ideas on coevolution and “natural human arrogance” seems to plant him firmly as a middle-of-the-road anti-humanist; not a bad place to be these days, considering the contemporary artistic void in these ideological regions. “To move away from the human obsession and to bring the smallest microbe to the forefront” is Durugadda’s stated goal, in life and in art.

But this practice of finding new meanings in form is a tricky one to formulate in language (again, a watermark of interesting contemporary art); verbally, it would seem that the abstraction of experience is Harsha’s goal, when really it is a modus operandi, a method of connection with the viewer. Freeing sculpture from traditionalist moorings, in this case, is truly an architectural practice, with scale being the only differentiating factor. Contemporary sculpture has become obsessed with scale- the idea that anything can be impactful if it’s big enough. Paul McCarthy, Jeff Koons, Louis Bourgeois, Vasconcelos, Chihuly… how many of the big names have made careers out of this simple premise? Scale offers instant prestige, and even more importantly, confers upon the artist that unique ability to make anything seem impressive, genius, necessary even (all of these, and perhaps Vasconcelos in particular, are complicit in a postmodern tradition succinctly identified by Lester Bangs in his 1971 review of a Captain Beefheart album- “pretenders by the truckloads have failed…to make the crucial distinction between art commenting on society and flat-out polemics.”) One can see in Durugadda shades of a different tradition, one that hasn’t been worked on or tinkered with since the days of Maria Martins, Giacometti, Henry Moore, and Hepworth. This is a tradition of natural evocation, a flipside to the contemporary discourse. When I heard his greatest influences were architectural, I wasn’t fazed in the least (in fact, the aforementioned sculptors emerged as points of reference later while shifting between observing and writing). The first associations that came to mind upon looking at his work were the alien yet natural structures of Frank Lloyd Wright (the Guggenheim in particular) and, especially, Antonio Gaudi. In their monumental work, scale is more incidental than a primary focus; if anything, it is a factor to be overcome, in order to bring a sense of intimacy and movement to something grand and necessarily stationary.

Harsha Durugadda’s work is neither grand nor stationary. The qualities he strives for and brings to the ever-widening world of 3-D art is, currently, largely unique; in the end, it’s the artist’s own words that describe his creations best- “I draw from dynamic living practices… whirling dervishes, Buddhist prayer wheels, fluttering of leaves- none of these are static forms. This is what makes my work occupy a more fluid form.” Indeed it does.

An interview with Harsha Durugadda by Dhani Muniz